Lower Limb Aponeurotic Injuries

What We Know, Don’t Know, and Their Potential Implications for Rehabilitation

Tim Rigby DPT, BSpSc, CSCS, ASCA L2

Soft tissue injuries are a frequent occurrence across various sports, significantly contributing to the number of days athletes missed from training and competition. A vast amount of research exists on injuries involving muscle/myofascial tissue and isolated tendon injuries. However, injuries involving the aponeurosis—remain underexplored. Despite its critical role in force transmission and muscle-tendon mechanics, the aponeurosis is often overshadowed in injury management and rehabilitation literature. This lack of understanding is particularly significant when considering how these injuries affect the rehabilitation process and return to-play (RTP) timelines.

The recent surge in attention to aponeurotic injuries is largely due to their potential impact on prolonged RTP and high recurrence rates (1,2). Notable examples include injuries to the central aponeurosis of the soleus, hamstring tendon-junction (T-junction) injuries, and “the de-gloving quadricep tendon injuries”. These injuries present unique challenges, not only for achieving timely RTP but also due to their complex structural and functional behavior. Understanding these complexities is essential for crafting more effective rehabilitation strategies.

The purpose of this article is to highlight current understanding, identify areas where knowledge gaps persist, and explore the implications these injuries have for rehabilitation. Hopefully this can provoke thought on how to best manage these complex injuries and pave the way for future research and practice.

Making Sense of the Terminology

To produce movement, force is transmitted from contracting muscle tissue to bone through a connective tissue network comprising the muscle-tendon unit (MTU), which includes both the free tendon and the aponeurosis. While the role of the free tendon in storing and releasing energy is well understood, the aponeurosis—often regarded as a broad sheet-like fibrous structure—has been less studied.

The aponeuroses are large connective tissue sheets that provide a scaffold for muscle attachment, with specific variations across different muscles (1).The aponeurosis is a continuation of the free tendon, linking muscle tissue with the extracellular matrix (ECM), including the epimysium and perimysium. It can be viewed as a force transmitter rather than a force producer (8,9) which may help explain why narrower aponeuroses in certain regions may predispose athletes to injury (1). Additionally, the terminology used to describe aponeurotic structures can be confusing. In different sports medicine environments, terms like central tendon, intramuscular tendon, septum, or intertendinous are often used interchangeably with the aponeurosis, making it challenging to distinguish between the different components involved in injuries.

Two key types of aponeurotic injuries are recognized:

Central myo-aponeurotic injuries: These occur within the intramuscular aponeurosis, surrounded on all sides by muscle fascicles and perimysium (e.g. central aponeurosis of the soleus).

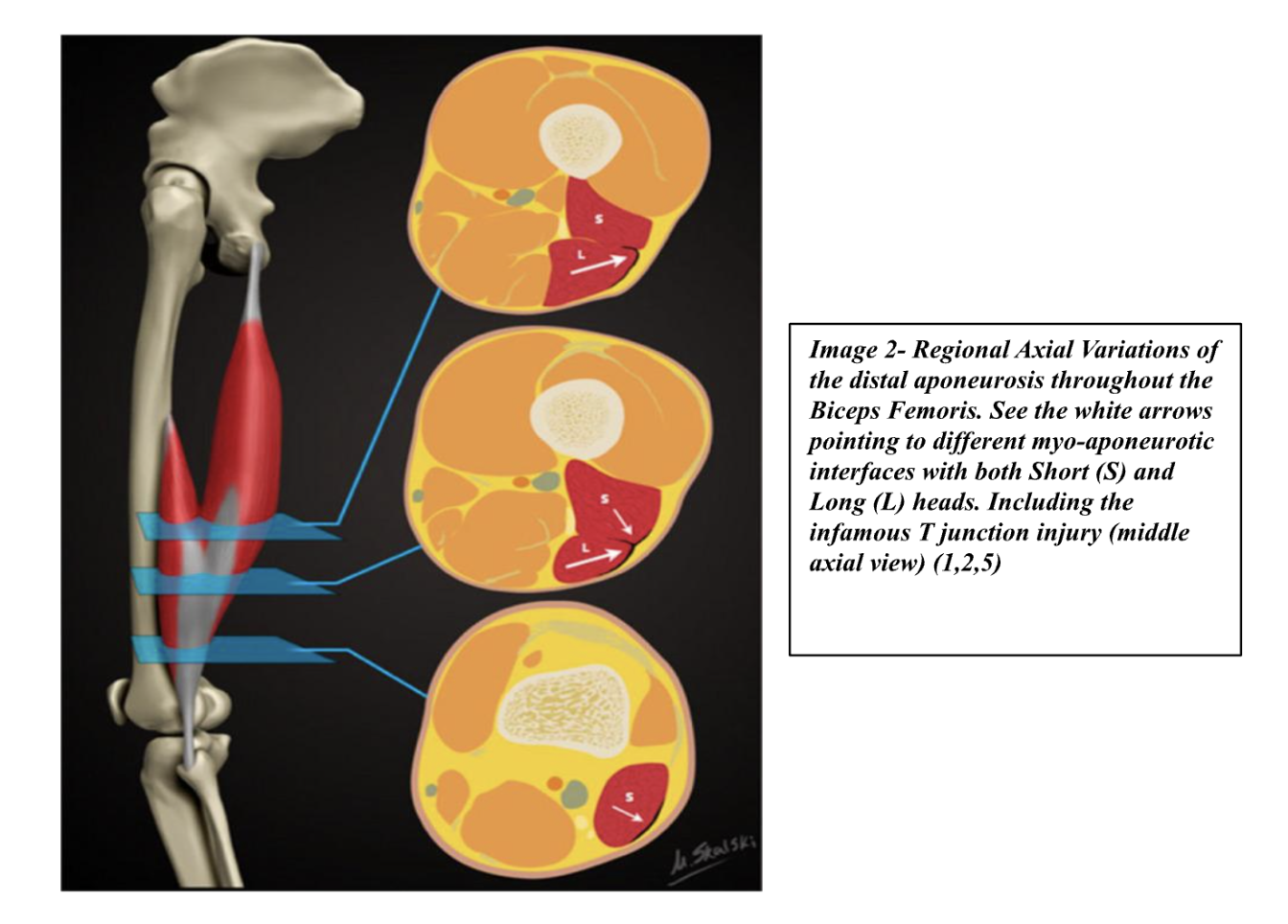

Peripheral myo-aponeurotic injuries: These occur on the muscle surface, such as the distal aponeurosis of the biceps femoris long head (BFLH).

Aponeurotic injuries can further be classified based on their orientation:

Longitudinal: The injury runs parallel to the muscle fibers.

Transverse: The injury cuts across the muscle fibers.

Mixed: A combination of both longitudinal and transverse injuries.

Transverse injuries can result in muscle retraction away from the aponeurosis, while longitudinal injuries typically do not. In severe cases, the muscle can shear away from its overlying aponeurosis, creating a gap between the two tissues. Understanding these injury classifications is critical, as they can differ significantly from traditional muscle-tendon junction (MTJ) injuries in terms of both healing time and rehabilitation strategy.

Unique Structure and Behaviour of the Aponeurosis

The aponeurosis is a unique tissue with variable structural and functional properties across different muscles and regions within the same muscle. The way the aponeuroses function— and their mechanical behaviour under load—varies significantly between individuals, making it essential to treat each injury based on its specific location and mechanical properties.

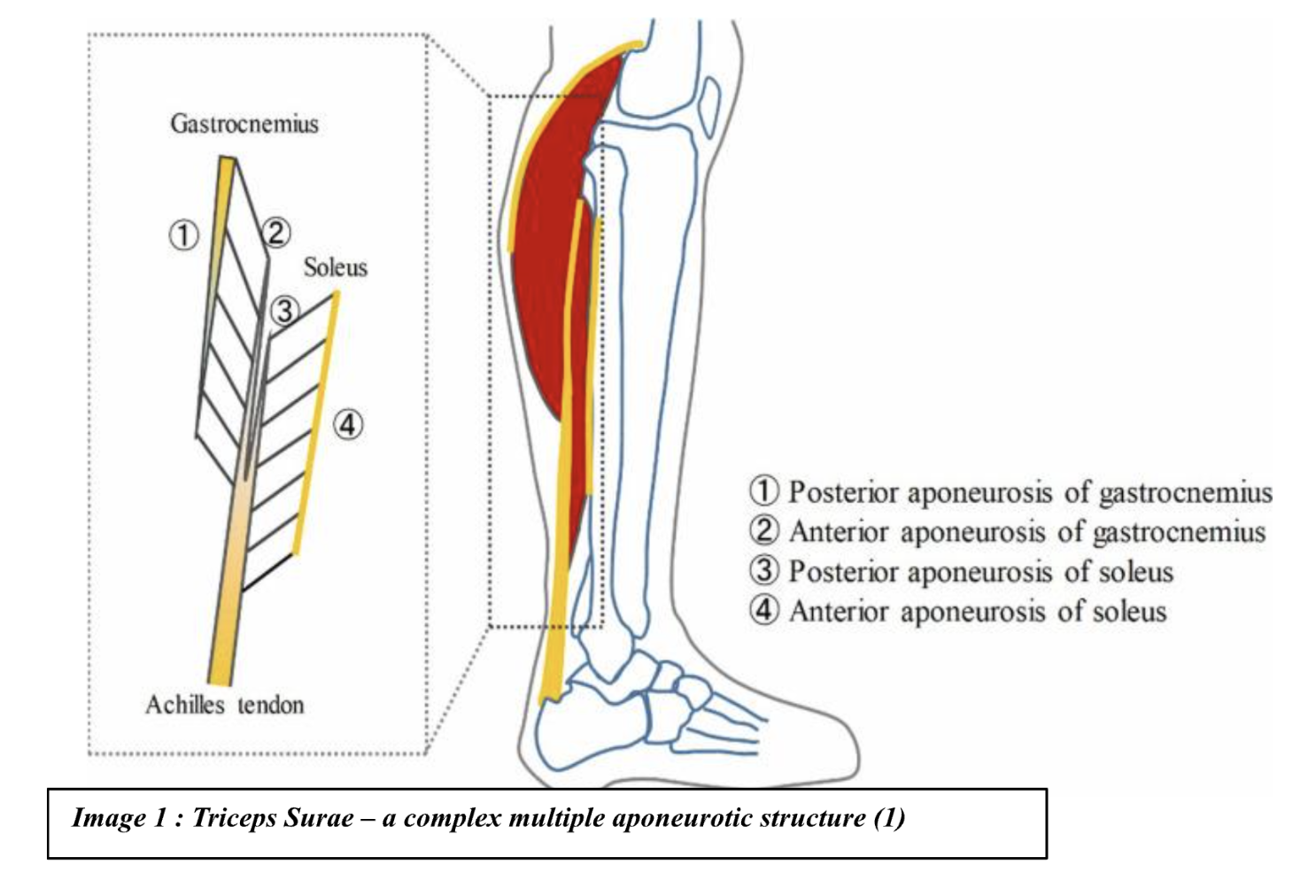

For example, the soleus has three aponeuroses (anterior, posterior, and central), while the gastrocnemius has two (anterior and posterior). In contrast, the hamstring muscle group has two aponeuroses: one for the biceps femoris long head (BFLH) and one for the semitendinosus (BFsh). The T-junction-based injury involving the shared aponeurosis of the BFLH and BFsh in the midsection of the muscle has been well-documented due to its high recurrence rates in certain sports (of up to 50%!). (1,2,10,11)

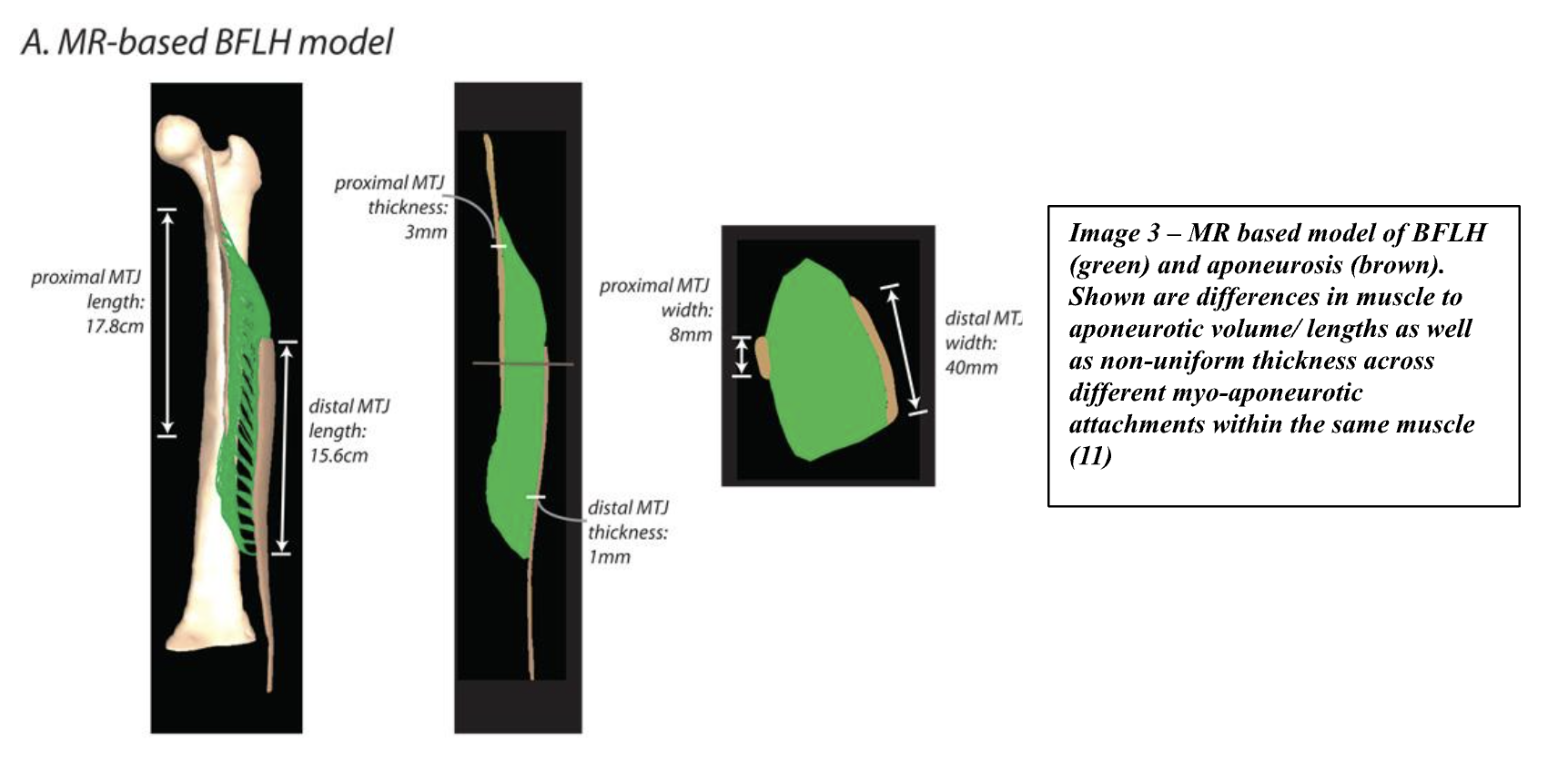

Additionally, aponeurotic structure varies across muscle types. For instance, the distal end of the BFLH becomes thinner where it transitions to the free tendon, while the aponeurosis is thicker where it joins the muscle. This difference in aponeurotic thickness across the length of the muscle has implications for how the muscle and aponeurosis bear mechanical loads.

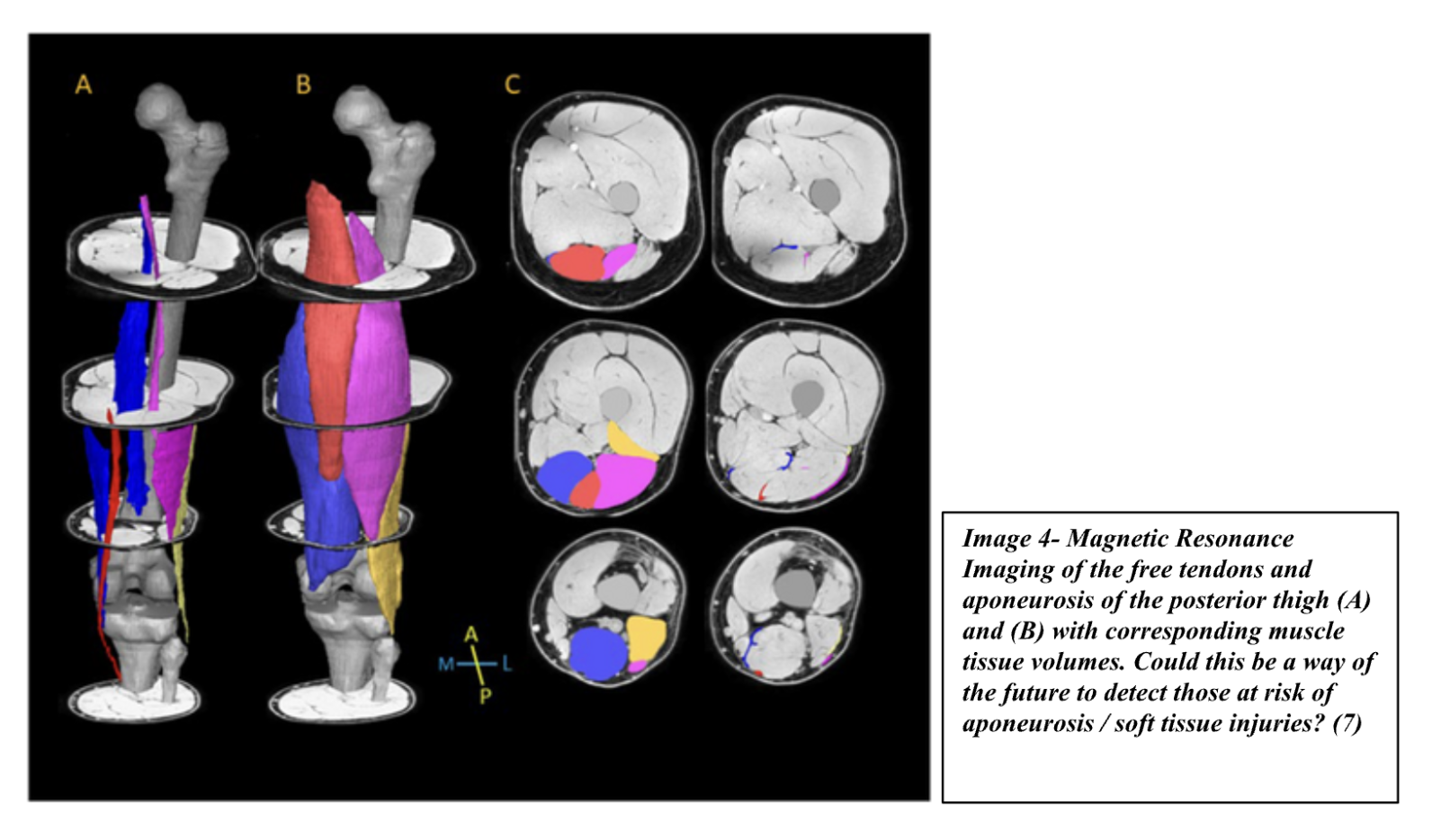

The aponeurosis also behaves differently under load compared to the free tendon. It deforms multiaxially, whereas the free tendon deforms uniaxially along its longitudinal axis. This is due to the complex muscle attachments, pennation angles, and changes in intramuscular pressure. Modelling studies suggest that a narrower aponeurosis (relative to muscle size) increases stress/strain at the myo-aponeurotic interface, especially during high-speed running or lengthened conditions. This concept of the muscle volume to aponeurosis volume ratio could influence injury risk and may be a critical target for rehabilitation. (8,9) Other studies have shown that an INCREASE in aponeurosis volume potentially from it becoming thicker (in response to an injury) could increase muscle fibre strain during contraction which could also have implications for re-injury risk.

One possible approach to rehabilitation could focus on increasing aponeurosis volume preferentially over muscle cross-sectional area (CSA), reducing the muscle-to-aponeurosis ratio. This might improve force transmission efficiency. While this remains largely theoretical, it offers a potential direction for future interventions.(6,7,8) Another approach could be ensuring we are restoring aponeurosis stiffness properties to reduce strain on the surrounding muscle fibres.(1)

The aponeurosis and free tendon are fundamentally different structures, both in terms of their mechanical properties and their function. Functionally, the free tendon is designed to tolerate high strain rates, allowing it to store and release energy effectively, with strains of up to 8%–10% during activities like running or jumping. This high strain capacity enables tendons to act as energy stores during movements. In contrast, the aponeurosis is much stiffer, with strains of only about 2%–2.6% in muscles like the triceps surae. This lower strain capacity reflects its role in force transmission, rather than energy storage. (5,6)

Further complicating things, the aponeurosis experiences longitudinal strain variability, with some areas shortening while others lengthen, along with lateral expansion of up to 5%. This lateral expansion is thought to result from oblique tension due to the pennate structure of muscle fibers, as well as the overall expansion of the muscle as it shortens. These complex strain patterns make the aponeurosis functionally different from the tendon, which primarily experiences strain along its longitudinal axis. (5,6)

When it comes to symptoms, pain at the tendon-bone junction is a hallmark of a free tendon injury. However, aponeurotic injuries have a more varied presentation. One key difference is the nerve supply; free tendons have sensory nerves located in the peritendon, the outer layer that provides sensation to the periphery of the tendon. In contrast, very little is known about the nerve supply of the aponeurosis, especially the deeper aponeuroses within muscles like the soleus. The central tendon in the soleus, for instance, is thought to have a poor sensory nerve supply, making aponeurotic injuries harder to diagnose clinically.(2,5,6)

Aponeurotic injuries in muscles like the soleus often present with vague tightness that progresses over time, or with sharp, acute pain. These symptoms can make clinical assessment more difficult and the prognosis less predictable. The variability in symptoms and the complexity of these injuries—especially when they involve deep or central aponeurotic structures—makes understanding their precise mechanisms challenging, and this in turn complicates treatment and rehabilitation strategies. (5)

Rehabilitation Implications

The rehabilitation of lower limb aponeurotic injuries requires an understanding of the tissue's structural and functional behavior. The optimal aponeurosis-to-muscle volume ratio remains under-researched, but as previously mentioned increasing aponeurotic volume may become a target in rehabilitation, similar to how muscle fascicle lengthening has been emphasized in muscle rehabilitation.(3)

Recent studies have explored how different exercise modalities impact aponeurotic adaptations. In the hamstring literature for example, recently a study showed how 12 weeks of lengthened-state eccentric training (seated leg curl) of the knee flexors has been shown to increase BFLH aponeurosis area by 9% , significantly more than the Nordic hamstring exercise 3%, while muscle volume changes were more modest (7). In the quadriceps literature some studies found that loaded SL knee extensions at approx. 85% of one repetition maximum (RM) (5 x 8 reps, 3 x p week) led to significant increases in aponeurotic width as well as other studies showing how a maximal isometrics knee extensor program for 8 week increased CSA by 7% whereas explosive knee extensions did not.(1,3,4,11)

These findings suggest that loading intensity, contraction type, and exercise selection should be carefully considered in rehabilitation programs targeting the aponeurosis. High mechanical strain (percentage of how much deformation) which has been found to increase stiffness more tend to have less of an effect on CSA (could benefit aponeurosis to muscle volume ratios).(6,7,8) As well as longer intervention durations (>10 weeks), may be necessary to induce meaningful changes in aponeurotic tissue. However, further research is required to clarify these relationships, as structural changes in tendon and aponeurosis do not always correlate with functional improvements.

Key Points of Interest

Aponeurosis terminology is complex and can be confusing, with different terms used to describe the same structures across sports medicine disciplines.

The aponeurosis is often confused with the free tendon rather than being seen as an independent structure.

The function of the aponeurosis differs greatly from a free tendon and seems to act more as a load transmitter and a regulator of muscle shape - being able to deform multiaxially vs only longitudinally like a free tendon does.

The structure of the aponeurosis varies not only between muscle types but also within a single muscle and between individuals, requiring individualized rehabilitation approaches.

Aponeurotic injuries are associated with longer RTP times and higher recurrence rates, underlining the importance of giving them a potential longer period for remodelling.

The volume and length of the aponeurosis relative to muscle size/volume may be a predictor of injury risk and could be a target for rehabilitation interventions.

Exercise selection and high mechanical strain is important in preferentially loading certain muscles to target aponeurosis volume over CSA.

Rehabilitation strategies may need to focus on increasing aponeurotic volume/stiffness and improving force transmission rather than purely targeted at increasing cross sectional area or capacity (6,7). However, this may not be a universal theme across all types.

Summary

The field of aponeurotic injuries is still evolving, with much to learn about their unique structural and functional behavior. While there are clear indications that injuries to the aponeurosis result in longer recovery times and higher recurrence rates, our understanding of the optimal rehabilitation protocols remains incomplete. As research continues, more refined rehabilitation strategies can be developed to improve outcomes for athletes recovering from these complex injuries. For now, maintaining a high degree of clinical suspicion and reasoning is essential, as athletes continue to benefit from the foundational principles of rehabilitation, including fascicle length, absolute strength and rate of force development. Future research will ideally help clarify the nuances of aponeurotic rehabilitation and guide clinicians in developing more effective, individualized treatment programs.

However, at the end of the day, when faced with complex injuries such as these, the athlete's clinical progression and region-specific physical milestones should take precedence over MRI findings. An MDT (multidisciplinary team) approach that uses robust criteria-based milestones is key to ensuring an athlete’s resilience, sturdiness, and successful return to sport. In elite environments, this system still serves as the foundation for decision-making.

References

Hulm, S., Timmins, R. G., Hickey, J. T., Maniar, N., Lin, Y.-C., Knaus, K. R., Heiderscheit, B. C., Blemker, S. S., & Opar, D. A. (2024, December 24). The structure, function, and adaptation of lower limb aponeuroses: Implications for myo-aponeurotic injury. Journal of Sports Medicine & Physical Fitness, 10, 133. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40798-024-00789-3

Green, B., McClelland, J. A., Semciw, A. I., Schache, A. G., McCall, A., & Pizzari, T. (2022). The assessment, management and prevention of calf muscle strain injuries: A qualitative study of the practices and perspectives of 20 expert sports clinicians. Sports Medicine - Open, 8, 10. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40798-021-00364-0

Eng, C. M., & Roberts, T. J. (2018). Aponeurosis influences the relationship between muscle gearing and force. Journal of applied physiology (Bethesda, Md. : 1985), 125(2), 513–519. https://doi.org/10.1152/japplphysiol.00151.2018

Finni, T., Hodgson, J. A., Lai, A. M., Edgerton, V. R., & Sinha, S. (2003). Nonuniform strain of human soleus aponeurosis-tendon complex during submaximal voluntary contractions in vivo. Journal of applied physiology (Bethesda, Md. : 1985), 95(2), 829–837. https://doi.org/10.1152/japplphysiol.00775.2002

Brukner, P., Cook, J. L., & Purdam, C. R. (2017). Does the intramuscular tendon act like a free tendon? British Journal of Sports Medicine, 51(5), 379-380. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2017-098834 6. Maeo, S., Balshaw, T. G., Nin, D. Z., McDermott, E. J., Osborne, T., Cooper, N. B., Massey, G. J., Kong, P. W., Pain, M. T. G., & Folland, J. P. (2024).

Hamstrings hypertrophy is specific to the training exercise: Nordic hamstring versus lengthened state eccentric training. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, 56(10), 1893–1905. DOI: 10.1249/MSS.0000000000003490

Lazarczuk, S. L., Collings, T. J., Hams, A. H., Timmins, R. G., Shield, A. J., Barrett, R. S., & Bourne, M. N. (2024). Hamstring muscle-tendon geometric adaptations to resistance training using the hip extension and Nordic hamstring exercises. Scandinavian Journal of Medicine & Science in Sports. https://doi.org/10.1111/sms.14728

Lazarczuk, S. L., Collings, T. J., Hams, A. H., Timmins, R. G., Opar, D. A., Edwards, S., Shield, A. J., Barrett, R. S., & Bourne, M. N. (2024). Biceps femoris long head muscle and aponeurosis geometry in males with and without a history of hamstring strain injury. Scandinavian Journal of Medicine & Science in Sports. https://doi.org/10.1111/sms.14619

Green, B., & Pizzari, T. (2017). Calf muscle strain injuries in sport: a systematic review of risk factors for injury. British journal of sports medicine, 51(16), 1189–1194. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports 2016-097177

Mok, K. M., & Bittencourt, N. F. (2020). A histoarchitectural approach to skeletal muscle injury: Searching for a common nomenclature. Orthopaedic Journal of Sports Medicine, 8(3), 232596712090909. https://doi.org/10.1177/2325967120909090

Rehorn MR, Blemker SS. The effects of aponeurosis geometry on strain injury susceptibility explored with a 3D muscle model. Journal of Biomechanics. 2010 Sep;43(13):2574-2581. DOI: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2010.05.011. PMID: 20541207; PMCID: PMC2938014.

About The Author

Tim Rigby DPT, BSpSc, CSCS, ASCA L2

Tim is a Physiotherapist, Strength & Conditioning coach who has been in the Sports medicine / rehabilitation field for over 10 years. He has worked with a variety of elite sport settings in both Australia and Canada including the Canadian Snowboard Team, Canadian Alpine Ski Team, Australian Triathlon team, Australian BMX Freestyle team as well as individual athletes from the NHL & CFL. He is currently employed by Queensland Academy of Sport (QAS) servicing Australian Olympic athletes based on the Gold Coast, Australia. He has a keen interest in lower limb injuries, in particular running related soft tissue injuries and how to best manage these.